Imagine the echoes of applause reverberating in the walls of an old café—the distant sound of coffee brewing and hands dancing on the strings of a well-worn guitar. In nearly half a century, Caffè Lena, located in Saratoga Springs, New York, and widely recognized as the oldest continually operating coffeehouse in the United States, has become an internationally renowned music venue. Lena Spencer would no doubt be proud of the lasting spirit her eponymous coffeehouse has brought to the community at large.

Since the 1960s, intimate listening rooms like Caffè Lena have played a central role in the politics and music of American folk culture. Not only are these places essential institutions in their own communities, but they are also of national importance, as American folk music has been and continues to be shaped and disseminated within their walls. A few of these venues have adapted to the changing music scene and beckon new talent onto their stages. They continue to exist because of performers’ desire to share their stories and songs with an audience and because of the dedication of certain individuals who aim to sustain the spirit of their communities. This is the legacy of Lena and her Caffè.

The child of Italian immigrants, Lena Spencer was born Pasqualina Rosa Nargi on January 4, 1923, in Milford, Massachusetts. In her youth, she spent weekends in New York City where she was introduced to jazz music and theater. She performed with an amateur theater group in Boston, worked in a rubber factory during World War II, and later served as a waitress in her father’s Italian restaurant. In her mid-twenties she held a position at a radio station, where she met future president John F. Kennedy on his campaign tour of Massachusetts. In 1958 Lena married Bill Spencer, a student and part-time instructor at the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts. Watching the folk revival boom around them in 1959, Bill Spencer had the idea of opening a folk coffeehouse as a moneymaking venture. According to Lena’s unfinished autobiography, the couple’s goal was to make enough money to retire in Europe. On May 20, 1960, Caffè Lena was born, with the Italian spelling of “coffee” to honor Lena’s Italian heritage.

Gandalf Murphy and the Slambovian Circus of Dreams performs at Caffè Lena in 2005. Photo: Joseph Deuel

Nearly fifty years later, what began as the business scheme of two struggling artists has become a place of national interest: the Library of Congress officially requested the Caffè Lena collection for its national archives. Michael Taft, head of the Archive of Folk Culture at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center explained in 2006:

The center has long been interested in the history and development of the American folk song revival movement. The Caffè Lena Collection, as one of the prime collections of its kind, fills in one of the missing pieces in this history—the role of coffeehouses and clubs in the folk song revival. . . . The center also has a personal connection with the Caffè, since its present director, Peggy Bulger, and its former head of the archives, Joe Hickerson, have performed there.

Well before his tenure at the Library of Congress, Gerry Parsons, Joe Hickerson’s former assistant, was a member of one of the earliest groups that performed at the Caffè.

Since 1960 the Caffè has provided a formative venue for performing folklorists, as well as for such influential artists as Bernice Johnson Reagan, Arlo Guthrie, Don McLean, Ani DiFranco, and Bob Dylan. But there is much more to Caffè Lena’s legacy than a laundry list of the big names in folk music who have passed through its doors. These musicians owe much to the Caffè’s longstanding tradition of showcasing a diverse array of up-and-coming but as yet unknown artists and providing a supportive community where artists can hone their talents. For this reason, Caffè Lena is an American treasure.

This year the Caffè celebrates its forty-seventh birthday at the same location on 47 Phila Street that it has occupied since its founding. Looking back at its venerable past, it is clear that the Caffè possesses an extraordinary history of innovation, multigenerational communication, and support for musical expression that transcends the lines of race, gender, and class. The Caffè’s history reflects a continuous merging of art, culture, and social action in the small city of Saratoga Springs. According to Field Horne, historian, former Caffè Lena board member, and Caffè patron since 1976, “As the years have passed, so much of mid-century Saratoga has been pushed out or to the side by the economic boom. The Caffè is one constant that we’ve been able to preserve. Further, it is an important institution for cultural preservation, which of course I have given a good part of my life to.”

Poster advertising forty-fifth anniversary concert at Caffè Lena. Photo: Caffè Lena Collection/Saratoga History Museum

Like-minded Caffè patron, folklorist, and musician George Ward has also dedicated a good part of his life to preserving the Caffè and the music it celebrates. Since the early 1960s, Ward has been a frequent Caffè performer, and since the early 1990s he has served as a board member. Ward’s skills as a trained folklorist have served the Caffè in many ways: “From time to time, I’ve been involved with one or another project to bring traditional artists to the Caffè who otherwise might not have come there, such as the McCullough Sons of Thunder from Brooklyn, New York, and the Julie Beaudoin Family.” Recalling his longtime involvement with Caffè Lena, Ward con- Gandalf Murphy and the Slambovian Circus of Dreams performs at Caffè Lena in 2005. Photo: Joseph Deuel tinued, “The Caffè was quite a focus for meeting people—both people who were folk or folklorists (or potentially so) and people who were more focused on building careers as singers. It was a place my wife, Vaughn, and I got to meet traditional artists as they were passing through, whether they were local or not.”

It was one particular local musician who influenced Ward initially to develop his relationship with Caffè Lena that has continued over the past four decades. “Probably the most significant influence on me as a folklorist,” he remembered, “was [traditional Adirondack musician] Lawrence Older, who may have been one of the people who told me about Caffè Lena. Going there with Lawrence and his wife Martha was something I did pretty regularly. Almost a self-taught folklorist himself, Vaughan and I actually learned quite a bit about fieldwork from Lawrence.” Ward went on to describe the importance of Caffè Lena as a location that enabled not only development of the skills of many would-be folklorists, but also the exchange of critical folk texts:

It was because of Lena’s that the world discovered Sara Cleveland, the great ballad singer. Sara’s son Jim loved the old songs that his mother sang; they were really part of his world. Jim would come to Lena’s particularly to hear people like Jean Redpath—people who sounded like traditional singers to him. At one point he brought one of Sara’s notebooks to show Lena, and Lena who was busy put them aside. Sandy Paton found them when they were performing at the Caffè, looked at them, and realized that Sara had some ballad texts that he had never seen before. So, he essentially said, “Lena what in the world is this?” Lena said, “That’s something Jimmy Cleveland brought by.” The rest, as they say, is history!

And history was certainly made: Sara Cleveland’s songs are now commonly sung by other folk singers who continue to perform her material at the Caffè today.

Over the years, Caffè Lena has fostered close ties to its neighbors in Saratoga Springs. Many poets and writers in residence at Yaddo artists’ colony have attended and participated in Caffè performances. Decades of student waitresses from Skidmore College have served Lena’s famous coffee and chocolate chip cookies to eager guests. The Pick’n and Sing’n Gather’n, a gathering of folks in the Capital District dedicated to the playing, singing, and sharing of folk and traditional music as a group and family activity often met to pick and sing at Lena’s. At the Fox Hollow Festival, Lena ran an ad hoc Caffè Lena outpost under a tent handmade from a parachute. Bill and Andy Spence, associated with the Old Songs Folk Festival, faithfully recorded shows at the Caffè for many years. A nationally syndicated radio program, “Live at Lena’s,” hosted by Peter Davis, ran on Albany’s regional public radio network, WAMC. And, for most of the Caffè’s years, historic Hattie’s Chicken Shack has been next door on Phila Street. Field Horne recalled, “Hattie always said to me, ‘Lena is a nice lady’—typical Hattie simplicity. They seem to have gotten along very well. They sort of watched each other grow old.” As the Caffè grows older, now without its founder to preside over the folk center she created, let us look back at the beginnings of the Caffè—a product of Lena’s loving, determined character and of the 1960s folk revival movement.

Lena Spencer. Photo: Joe Alper, courtesy of the Alper family

Lena and Bill Spencer, then living in Boston, chose Saratoga Springs as the site for their new coffeehouse after Bill visited the town with one of his art students during Skidmore’s family weekend. During the first two years of Caffè Lena’s existence, Lena and Bill took weekly trips to Boston and New York to scout out the latest folk talent for their new venue. Mississippi John Hurt, Bernice Johnson Reagon, Jackie Washington, and Hedy West were just a few artists discovered by the Spencers for their new “bohemian” coffeehouse in Saratoga. A close connection with Dave Van Ronk—one of Lena’s favorite musicians—led to the booking of a then-unknown Bob Dylan in, according to varying sources, 1961 or ’62. To Lena and Bill, Dylan was nothing more than a young singer with a penchant for Woody Guthrie songs and a harmonica tucked into his back pocket in need of a place to play. Sarah Craig, Caffè Lena’s manager since 1995, observed, “Caffè Lena was born out of New York’s and Boston’s folk scene. The values of the wider movement—respect for folk tradition, simplicity, the passing of music from person to person, sticking together—became the core values of Lena and her Caffè. To this day, despite so many changes in the wider world, we stay true to that original spirit.”

In 1962, Bill Spencer left Lena to run the Caffè alone, with the help of an extended family of volunteers. The Caffè’s community spirit has persevered. For over four decades, Caffè Lena has joined other legendary folk venues like Club Passim (formerly Club 47) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley, and the Bluebird in Nashville in providing a place where new and established musical performers are showcased. Together these clubs have produced a generation of performers, festival organizers, and managers. “Caffè Lena could not keep roots music alive all on its own. There needs to be a nationwide network of strong, excellent venues where people can share their art,” Sarah Craig emphasized. All of these venues were enormously influential during the 1960s folk boom and claim important roles in America’s musical and cultural history, but only Caffè Lena has never changed names or locations. The Caffè also has its very own black box theater, a separate room adjacent to the Caffè’s folk music performance space where it presents plays.

Lena Spencer. Photo: Joseph Deuel

One key element of Caffè Lena is its strict no-alcohol policy, in place since its founding. “We worry that to serve any alcohol would make it harder to maintain the silence during shows so we’ve chosen against it, despite the attraction of the revenue that it would bring in,” explained Craig. Other long-running listening rooms such as the Bitter End in New York City, the Ark in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the Iron Horse in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Godfrey Daniels Coffeehouse in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, all serve or permit alcohol. A few, notably the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley and the Swallow Hill Music Association in Denver, stay alcohol-free as a rule, but occasionally purchase a liquor permit for special events. When asked how banning alcohol changes a club’s atmosphere, Steve Baker, executive director of the Freight and Salvage noted, “It triggers a serious change in the nature of the club as a consequence: [a change] in the composition of the audience. [With a no-alcohol policy] we end up being more family-oriented . . . seeing three generations at once.” Eryn Hoerig, front desk manager at the Swallow Hill Music Association agreed: “There are plenty of clubs that serve alcohol and music at the same time, but [by not serving alcohol] we see it as a chance to set ourselves apart. It makes us kid-friendly.”

Another aspect that seems to set Caffè Lena apart as a premier listening room is its commitment to valuing community over business. Today, Caffè Lena is run by a nonprofit board of directors that took over shortly after Lena Spencer’s passing. The board relies on members, donors, and volunteers for support. Caffè Lena has roughly four hundred dues-paying members and a pool of one hundred volunteers. According to Sarah Craig, “One thing that’s true about Caffè Lena is that there’s always a way for people to hear the music, whether they have money or not. If need be, they can get a small job at the Caffè in order to attend a show. The theater program won’t turn away kids if they can’t pay. We find a way to get them involved. Keeping true to Lena’s vision, we continue to take risks on musicians we believe in, always placing our artistic mission above short-term profit.” Torey Adler, former president of Caffè Lena’s board of directors, notes Lena’s community-oriented influence in the character of the Caffè: “Lena was and continues to be the root of everything we do. The only way to maintain what she started is to understand where it all came from. If we forget Lena, we risk becoming just a business, where music is exchanged for money. There are enough places like that already.”

Caffè Lena has remained small and intimate, where the audience is close enough to feel as though they are part of the art. “Sometimes we inherit folks when the commercial world has sidelined them,” Sarah Craig noted. “Of course the experience of seeing them at Lena’s [versus a larger venue, like the Saratoga Performing Arts Center] is like the difference between seeing a play versus seeing a movie. Here it’s intimate, intense, and interactive. You hear the intakes of breath, feel the vibration of a foot keeping rhythm.” Club Passim’s booking manager Matt Smith agrees: “[At these venues] performers are treated better by staff/audience and also make more of a connection to the audience. It’s hard to perform well when there’s still a TV playing at the bar.”

The history of Caffè Lena demonstrates the growing significance of grassroots folk music and provides a view of a community-oriented folk revival movement that began in the early 1960s and continues to the present day. Torey Adler remarked, “The Caffè is entirely a product of the ’60s folk movement. It wouldn’t exist otherwise. I think the Caffè’s current programming strategy is one which has evolved organically from Lena’s old schedules, which grew out of her awareness of and connection to the larger folk scene in the ’60s.”

Baba Israel and Dawn Crandell lead a youth workshop at Caffè Lena in 2005. Photo: Jocelyn Arem

The legacy of Lena Spencer continues today. Skidmore College, as much as her small Caffè on Phila Street, continues to feel Lena’s presence. Lena helped Skidmore students in 1973 found the student-run campus coffeehouse, “Lively Lucy’s,” which still exists today and hosts an annual spring folk festival. In the 1970s, Lena hosted a radio show, “Lena’s Open Door,” on Skidmore’s campus radio station.

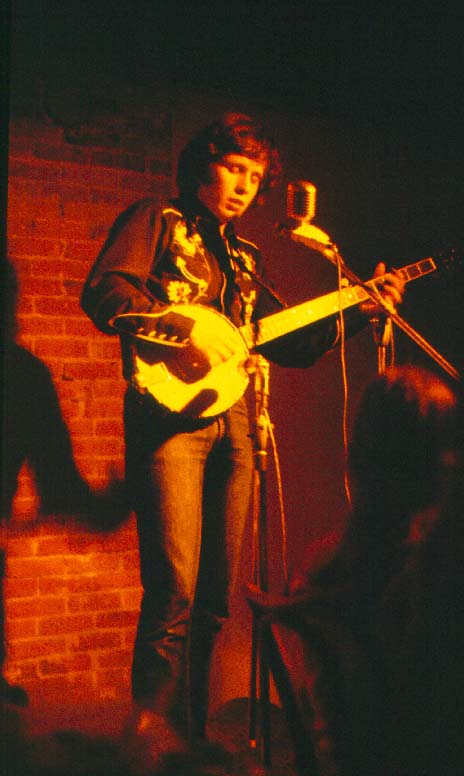

Don McLean at Caffè Lena. Photo: Joseph Deuel

The college honored Lena in 1987 with an honorary doctorate of humane letters. Lena’s on-screen debut also came in 1987, when she played a “slatternly woman” opposite Meryl Streep in Ironweed, a feature film based on the book by William Kennedy. The city of Saratoga Springs honored her talents and contributions that same year, renaming Hamilton Alley as “Lena Lane.” On March 15, 1989, Lena was honored with the Saratoga Arts Council’s first lifetime achievement award. Over the years there have been a number of Lena Spencer days declared by the city of Saratoga Springs.

Lena’s legacy lives on in the management skills of its current manager, Sarah Craig, and its nonprofit board of directors. Craig reflected, “I keep the core very similar to Lena Spencer’s, but also keep my ear out for new artists that are branching off from the roots in fresh ways. These performers are intellectual geniuses, admirably independent, full of determination, talent, courage. It’s wonderful to have these people in my heart as I go through life.”

In 2008 Caffè Lena will begin a campaign to renovate its historic building on Phila Street and equip it with handicap access. As the Caffè prepares for a much-needed facelift, its archives are now being preserved through the Caffè Lena History Project, which has recently joined forces with the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress to document the impact of Lena’s legacy on America’s cultural history. “It is important to me that we pass on what we know about Lena’s Caffè in a way that endures over the years, and that people who were close to Lena stay close to the Caffè,” Torey Adler explained. “I always hope that Lena would approve of how the Caffè carries on her tradition. There is a heart to Caffè Lena. If it stopped, we would all know.”